The Problems of Expansion

While Rome was fighting the Punic Wars in the west, its

forces were also engaged in the east. Between 230 BC and

130 BC, Rome brought the entire eastern Mediterranean area

under its influence. As a result of this conquest, Romans

began referring to the Mediterranean as mare nostrum— "our

sea." Because Rome now controlled a vast area, the

republic and its government had to change. It remained

a republic, but the Senate gained almost complete control

over the army and foreign policy. The nobles gained even

more power.

The Romans loosely governed the new territories, called

provinces. They did not allow the people of the provinces

to become citizens, nor did they make them allies. Instead,

the Romans simply made the people of each province subjects

of Rome . Each province was administered by a governor

who was backed by the power of the Roman army. Some provincial

governors took bribes and paid little, if any, attention

to the needs of the people. In addition, tax collectors

tried to squeeze as much money as they could from the provinces.

Rich, Poor, and Slavery

The Romans also had problems at home. The Roman farmer-soldiers

who returned from the Punic Wars were sickened to find

their livestock killed, their homes in ruins, and their

olive groves or vineyards uprooted. The farmers did not

have enough money to restore their farms and thus had little

choice but to sell the land to wealthy aristocrats.

Many of the farmers who lost their land moved to the

cities. Not all of them could find jobs there, however,

and they depended on the government for food. In contrast,

trade within Rome 's vast empire had created a class of

business people and landowners called equites (EK-wuh-teez).

They had great wealth and political influence. Within the

republic, the gap between rich and poor, powerful and powerless,

continued to grow.

As time passed, Rome became dependent on the provinces

for grain, its chief food. Turning agriculture into a profitable

business, the aristocrats created large estates called latifundia (LA-tuh-FUHN-dee-uh)

that provided grain, sheep, olives, and fruits for urban

markets. Labor for the latifundia was cheap because

Rome 's conquests brought thousands of captives and prisoners

of war to work as slaves. By 100 BC, slaves formed about

30 percent of Rome 's people.

As slave labor replaced paid labor, thousands of small

farmers and rural workers poured into the cities seeking

employment. Jobs, however, were not readily available,

and the new arrivals gradually formed into a class of urban,

landless poor. Angry and without hope, the urban poor eked

out a meager living and supported any politician who promised "bread

and circuses," cheap food and free amusements.

The Gracchi

It became increasingly obvious that the Roman Republic

was unable to meet these enormous challenges. Brave

leaders attempted to reform the government, but the days

of the republic were numbered.

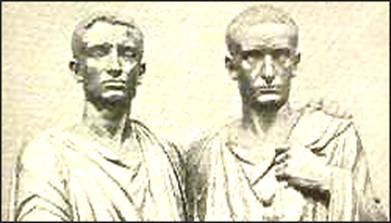

Two brothers, Tiberius and Gaius (GAY-uhs) Gracchus (GRAK-uhs),

saw the need for reform. Together the brothers were known

as the Gracchi (GRAK-ee) . They were the sons of a famous

patrician father, Tiberius Sempronius Gracchus, twice consul

and censor, and a patrician mother, Cornelia, the daughter

of the legendary war hero Scipio Africanus the Elder who

had defeated Hannibal during the Second Punic War.

Together the Gracchus brothers ruled Rome during the

period of roughly 133 to 121 BC, a time just after Rome

had endured nearly a century of repeated wars of conquest. The

Roman machinery of government, directed by the patrician

Senate, had become increasingly ineffective in dealing

with its overseas dominion and in dealing with the problems

that gaining a territorial empire had caused at home. Together the Gracchus brothers ruled Rome during the

period of roughly 133 to 121 BC, a time just after Rome

had endured nearly a century of repeated wars of conquest. The

Roman machinery of government, directed by the patrician

Senate, had become increasingly ineffective in dealing

with its overseas dominion and in dealing with the problems

that gaining a territorial empire had caused at home.

Tiberius was elected tribune in 133 BC. He was deeply

troubled by the fate of the farmer-soldiers who lost their

land. He proposed limiting the size of the latifundia and

distributing land to the poor. Although these suggested

land reforms made him popular with the common people, they

angered and frightened many senators. The Senate, made

up of the wealthiest Roman patricians, opposed the reforms

of Tiberius. A mob of senators and their supporters clubbed

Tiberius and hundreds of his followers to death.

Gaius was elected tribune in 123 BC and again in 122

BC. He used public funds to buy grain, which was then sold

to the poor at low prices. This and other acts outraged

the senators, who sought to cancel some of the laws Gaius

had passed. Ten years after the murder of Tiberius, Gaius

and many of his supporters were killed in a riot. The deaths

of the Gracchi marked a turning point in Roman history.

From this point on, violence replaced respect for the law

as the primary tool of politics. Army leaders came to power

in Rome . The period of violence that was introduced by

the combination of the Gracchi followers and the power-hungry

senators and aristocrats helped to bring an end to the

Roman Republican system of government.

The Social War

During this period, Rome 's relationship with its allies

throughout the Italian Peninsula entered a crisis. Citizens

of the Italian cities had served in the Roman army and

had endured much hardship in defense of Rome during the

Punic Wars. The ruling groups of these cities wanted to

share in the benefits of Rome 's growing power. Above all,

they wanted the right to hold public offices in the Roman

government, and they called for Roman citizenship. The

Senate, however, sought to maintain its hold on power and

stubbornly resisted the allies’ demands.

Finally, in 91 BC, the allies rebelled. The war that

followed was called the Social War, from the Latin word socius,

meaning "ally.” Many of the allied cities' troops

had served with the legions and were as well trained and

disciplined as the Romans themselves. Thus, the war that

followed was one of the bloodiest in Rome 's history. Ultimately,

Rome won. The Senate, however, finally agreed to the allies'

calls for citizenship and political participation. With

this decision, people throughout Italy began to view themselves

as Romans, and the Roman state grew to include the entire

peninsula.

Generals and Rebels

Gaius Marius, a Roman general who was elected consul

in 107 BC, brought major changes to the Roman political

scene. Marius became a consul after saving Rome from attack

by Germanic tribes. Because the dwindling number of small

farmers had made a citizen army (made up of landowners)

obsolete, Marius turned to the unemployed urban poor to

build a new army. Unlike the citizen soldiers, Marius's

recruits were paid, given uniforms and equipment, and were

promised land when they had finished their military obligation.

As a result of Marius's action, Rome for the first time

had a professional army in which soldiers owed allegiance

to their commander, not to the Republic.

To advance their political ambitions, rival military

and political leaders formed their own separate armies

and used them against each other. From 88 BC to 82 BC,

Marius and a rival general named Sulla fought for control

of Rome .

In 88 BC Lucius Cornelius Sulla was elected consul. After

his term expired, he wanted to take a military command

that promised to gain him great fame and fortune. His enemies

in Rome , led by Marius, tried to prevent him from doing

so. Sulla responded by marching on Rome , an action that

led to civil war. Sulla finally drove Marius into exile,

and from 82 BC to 79 BC Sulla ruled as dictator. Sulla

tried to restore power to the Senate, enlarging it by 300

members and giving it complete control over the government.

Uprisings lead to Stronger Leaders

As the gap between rich and poor steadily widened, upper-class

Romans lived with the constant danger of revolts. To quell

mounting unrest, Rome stationed legions in most provinces.

Even Italy was not safe from uprisings. From 73 BC to 71

BC, an army of 70,000 slaves led by the slave Spartacus

plundered the Italian countryside in an effort to win freedom.

With great difficulty, the Roman legion of a general named

Pompey finally crushed the uprising and killed about 6,000

of Spartacus's followers, crucifying them along the Appian

Way (Rome’s most famous road).

Putting down the many revolts cost Rome troops and money

and placed a strain on its resources. It also led people

to allow military leaders to become increasingly powerful

in hopes that peace and order could be achieved. More and

more, however, any army commander with loyal troops could

force the Senate to do his bidding. This practice of using

the army to gain political power was copied by a rising

young politician named Julius Caesar.

|